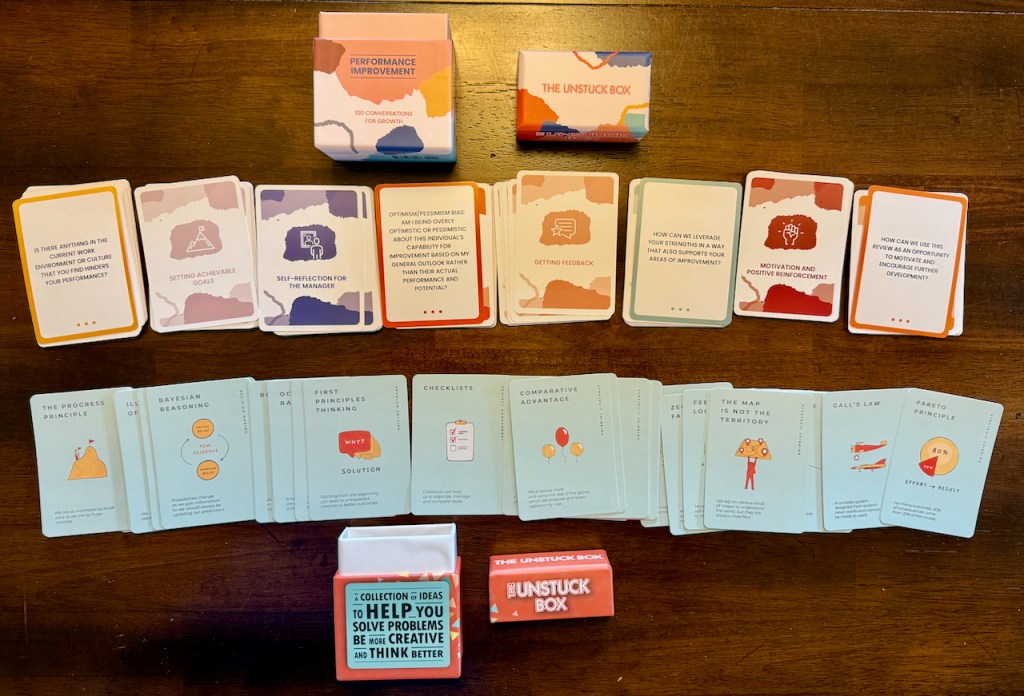

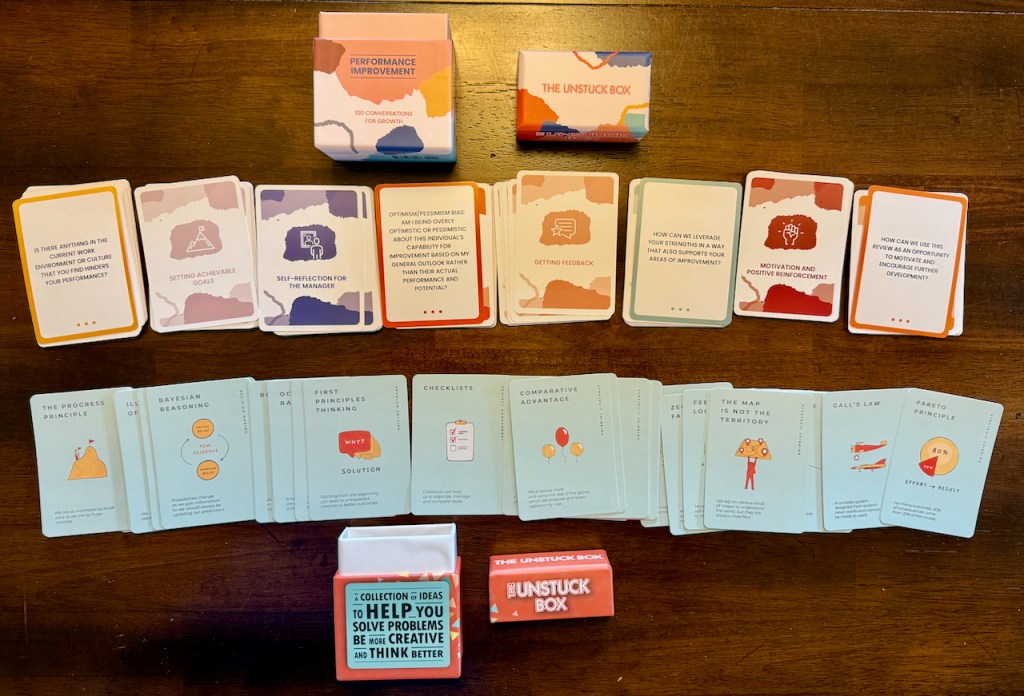

Resources that may fuel your journey. The Unstuck Box offers playing card-style professional development tools to facilitate conversations that matter. These are a positive addition to the consulting and facilitation toolbox.

Resources that may fuel your journey. The Unstuck Box offers playing card-style professional development tools to facilitate conversations that matter. These are a positive addition to the consulting and facilitation toolbox.

When your priority is managing numbers, inputs on a spreadsheet are all that are required. If you lead people, you must prioritize a human-centered approach and balance resources. One is easy, but the results are not visible until the numbers equate to human action. The other is more challenging but builds trust and loyalty, which means people deliver more than the resources provided.

Your choice.

I read a social media post that I cannot relocate, suggesting that what allows a choir to hold a note for an impossibly long time is that each singer can drop out and take a breath before resuming. As long as breaths are interspaced so they do not all overlap, the audience hears a consistent note, and the choir members achieve their goal of performing the music as composed.

The author took the choir analogy to discuss social activism and that volunteers and teams can achieve constant pressure if they act and then take a break as long as other individuals are committed to the process. The totality of overlapping efforts is not being ‘always on’ but rather being ‘in the game.’ The phrase ‘fight forward’ has been a guiding mantra for many social sector organizations. We cannot fight back against all the events that have transpired, but we can fight forward. We can be engaged in creating the best version of ourselves and our community while recognizing that our past versions have left room for improvement.

If your strategic planning attempt reflects playing the strategy game Battleship, then the prospects of success are limited. The possibilities of arranging the ships on the board are vast. This is akin to selecting the strategies and goals in a traditional plan. Then, we must start guessing in some methodical or random order to hit the correct positions and create an impact. The calculations behind the probability are significant.

There are a surprisingly large number of ways that the ships could be arranged: for example, a blank board with the usual 5 ships has 30,093,975,536 possible configurations. Source C.Liam Brown

What if we adopted a more durable approach? What if our goal was not to ‘win’ strategic planning but to remain in the game (and mindset) of planning and amending. What if the act of thinking strategically was a sign of progress? What if we collaborated with others instead of playing in a silo? What if we relied on others to succeed so that we could thrive?

Hagrid offers Harry Potter two choices: to follow him to enroll in Hogwarts or to stay with the Dursley family. The story (and film franchise) would have been very different if Harry had chosen to stay with the Dursleys.

We are presented with the same opportunity daily. Although the magnitude of our decisions might differ daily, we can stay or go.

How do you approach ‘unless you’d rather stay’ options?

If you search Google Maps for the Gulf of Mexico, you will generatedifferent results depending on which country your search originates in. A United States search delivers the Gulf of America, and a search in Mexico reveals the Gulf of Mexico. Regardless of the politics behind this naming dispute, it is a quick illustration that we might see the same thing but have different ways of articulating the answer.

When is it acceptable to use other people’s ideas for your enterprise’s benefit? In the social sector, an homage (or straight-out plagiarism) is acceptable in some circumstances. A successful gala becomes a template for others to replicate. An annual appeal (or annual report) is quickly adopted by peer organizations. A new source of engaged and effective board members is mined heavily by numerous causes. Network affiliates frequently hire (poach) development and marketing professionals from their peers, asking them to replicate successful campaigns.

However, there are times when fishing from another organization’s pond can be problematic. Attempting to recruit an Executive Director navigating the crux of stabilizing a local nonprofit or intentionally scheduling a last-minute ask (cutting the line) with a major donor just before another enterprise makes their pitch for a leadership campaign gift. Or a board member who takes confidential information from one meeting to another cause, foregoing their duty of loyalty to the source of the information.

How might we establish processes that allow the sector to thrive and our peers to succeed but retain our superpower to fuel the journey we have embarked upon? What trip wires and circuit breakers have you established to balance fidelity and partnership?

Flying back to the United States from Europe, our flight path crossed the Arctic Circle, traveled north of Iceland and across Greenland, and dropped down into Canada. I have been close to the Arctic Circle on land adventures but have never crossed the line of demarcation at ground level. If somebody asks if I have been above the Arctic Circle, technically, the answer is yes, but the answer is not what I would consider authentic.

How might we ask more intentional questions when seeking a factual answer? How might we remain curious rather than accepting the first response we receive?

A few years ago, a friend and I made dinner reservations at a hotel restaurant. We had just eaten breakfast and noted that the mountains and snow-covered valley views from the tables by the big windows were remarkable. So we requested a window table if possible. When we arrived for dinner, we were seated at a window table, but we had forgotten to account for the fact that sunset occurred so early in the winter season. We sat at the window table for our meal but could only stare into the night.

Sometimes, we make plans, assuming the views will be amenable to our experience. When an obstacle appears (weather, daylight, misaligned window, selecting the wrong side of our mode of transport), we must be content with the outcome. Planning can be tricky, and we are not guaranteed the results we outlined before arriving in person.

How might we be adaptable to the environment? How might our entire plan not hinge on a single attribute or assumption?

When your core values cannot stand a policy change, perhaps the value statements were taglines rather than behaviors embedded in your enterprise’s actions. Values should endure the good and the bad, not just the latest public poll.